I wonder if the NZ Herald paywall has had any impact on the NBR? Anyone know? It’s probably not a zero sum game, but even so.

a Huawei thought

Navigating the Huawei story is one of the toughest jobs in technology journalism at the moment. There are many facts and statements, lots of suppositions swirling around, but no smoking guns, no hard evidence of wrong doing.

Huawei may have a case to answer, but that question is almost submerged now. A lot of damage is already done, not just to Huawei but to supply chains as well. I can’t ever remember seeing a company taken down like this before. One danger is that it could have created a precedent. Who might be next?

Amazed that those people who constantly talk about the power of “market forces” can’t draw a straight line between teacher’s pay and teacher shortages.

Orcon first to trial residential 10Gbps broadband

I’m impressed. Orcon makes a fetish of being the fastest, geekiest ISP, this is another feather in its cap.

12 years with WordPress. I started about the time of the first iPhone.

Last night I was thinking: “Why didn’t Samsung’s DeX pad do better". On paper it looks great but it doesn’t seem to have fired up the market. Then I remembered how dreadful Android can be on anything other than a phone.

That moment when you wonder “do I have a cold coming on?” Then check there’s at least one lemon and a pot of honey in the kitchen.

One of my biggest frustrations with the iPad, and a reason I can’t drop using a tradition computer yet, is that it’s difficult to do something trivial like copy a document from OneDrive to Dropbox. Never mind what you think of OneDrive and Dropbox, it’s a productivity barrier.

Pile on.

Microsoft removes Huawei’s MateBook X Pro from its online store, stays silent on whether it will prevent Huawei from obtaining Windows licenses for its devices (Tom Warren/The Verge) www.theverge.com/2019/5/21…

The Most Expensive Lesson Of My Life: Details of SIM port hack

He lost US$100 grand in cryptocurrency through his phone… yikes.

Any other New Zealand folk on micro.blog?

Is anyone out there working on ways to integrate this into a WordPress site?

Also, I like the idea of bringing back webrings. Researching that will keep me out of mischief this weekend.

Matthias Ott just reminded me to check the microformat stuff was working on my billbennett.co.nz site (it wasn’t).

These things are important.

I can do about 95 to 97 percent of the things I need to do on my iPad Pro, the main problem stopping me from going all in is web-based aps that insist on treating the iPad like an iPhone.

Pretty soon I’m just going to cut those apps from my life.

The term “content” is a barbarism that bit by bit devalues what journalists do.

- Jay Rosen, Chair of Journalism at New York University

Is there a semiologist out there? I’m interested to know why the poo emoji is smiling.

Netflix is the ultimate embodiment of Bruce Springsteen’s “57 Channels and Nothing on”.

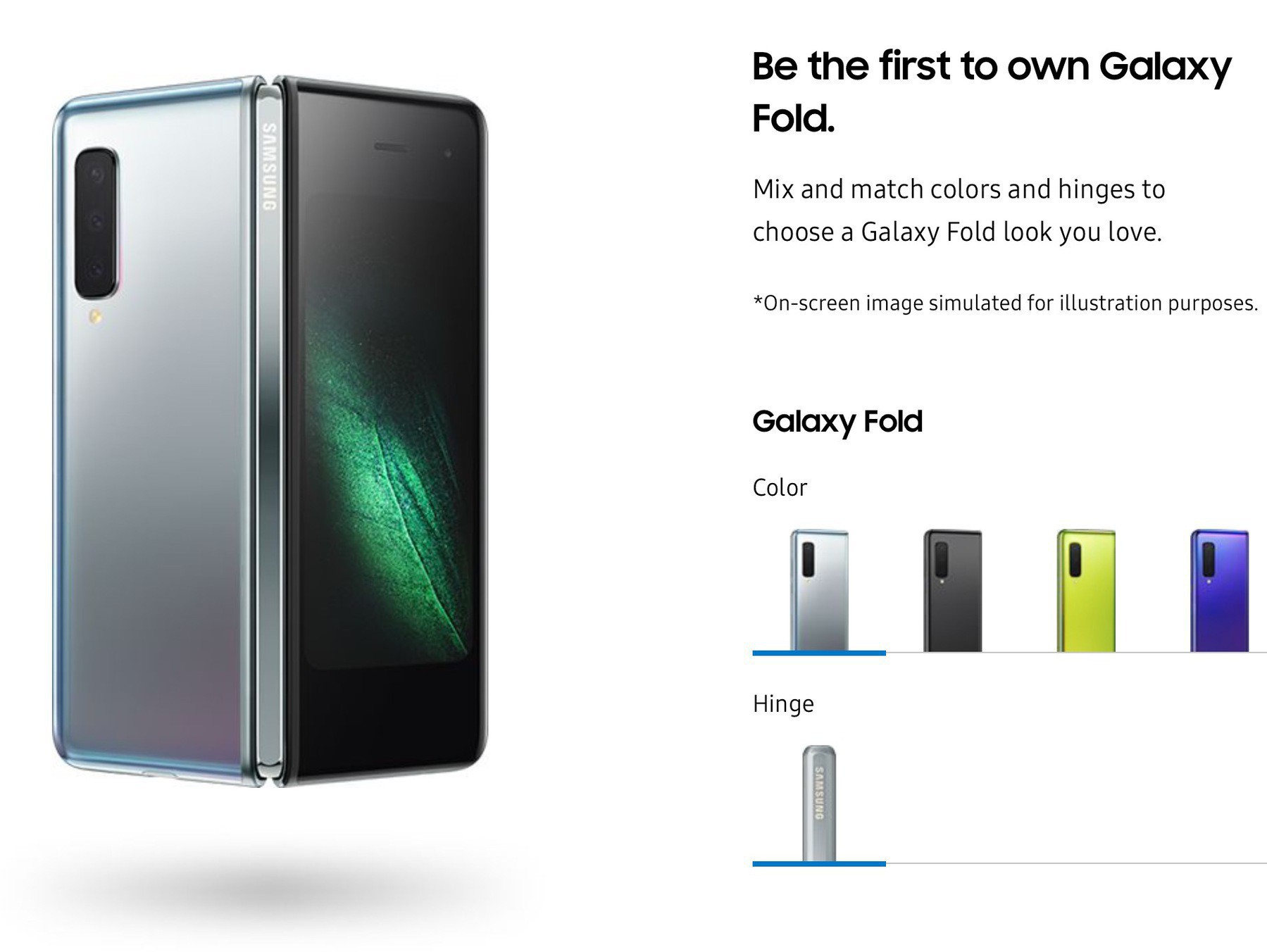

May not be wise if the reports of screen breaks on review machines extend to the production run.

Huawei P30 Pro review update

Added this postscript to my Huawei P30 Pro review. billbennett.co.nz/p30-pro-r…

When I reviewed the P30 Pro, I charged the phone with a USB-C cable that I already had set up for other devices. In part that was because the phone was supplied with a Chinese power supply.

While packing the phone up to return to Huawei, I tested the supplied USB-2 to USB-C cable. It doesn’t work.

This is an example of sloppiness that you wouldn’t expect to find with rival brands and goes some way to explain why Huawei’s core mobile network business faces problems. billbennett.co.nz/huaweis-e…

“You may wonder if there’s a market for a 7.9-inch iPad when you can buy a 6.5-inch iPhone.”

Well yes there is. It’s bigger than you might think.

Started working on a review of the Audiofly AF56W wireless headphones. One of the points I was planning to make was that they are harder to lose than the Apple AirPods.

Went out for coffee. Came back to carry on testing.

I think you can guess what happened next.

Stuff makes a spat over development sound like an assault.

Agree. Also, the headline does that clever “show not tell” thing….

‘APPL STILL HASN’T FIXD ITS MACBOOK KYBOAD PROBLM’